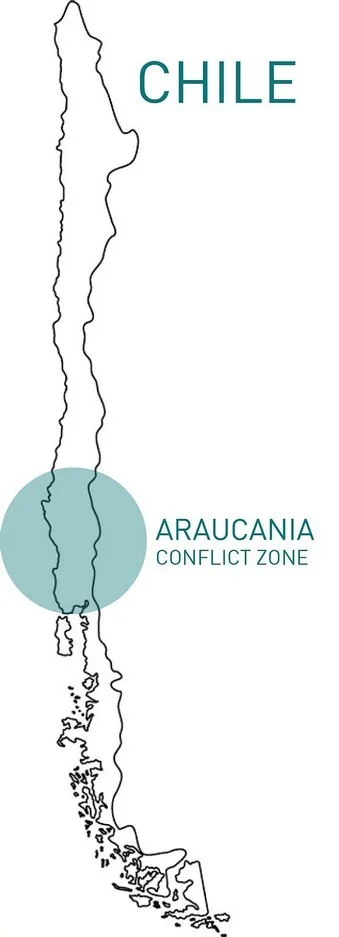

Araucania Conflict Zone - Chile

Missions > Monitoring > South America

H.E. Candidate to the presidency request International Human Rights Commission to stop the militarization of the Araucania region

H.E. Candidate to the presidency request International Human Rights Commission to stop the militarization of the Araucania region The new conquest of Araucania

The decision to send the military to Araucania is an act of the utmost gravity: for the first time since the return of democracy, their participation in crime control is justified. The consequences of taking this step could be terrible. This shows how the relationship of the Chilean State with the Mapuche people is marked by brutality disguised as civilization.

Chile's political and economic elites have not varied much in their strategy towards the native peoples. Occupation, integration, and repression have been the guidelines that delimit their political action. Although the dominant racist discourse of the 19th century has been partially modified, the same vision of the indigenous "question" prevails. The government's decision this week to transfer the armed forces to the zone is perhaps the crudest manifestation of the resounding failure of the timid attempts to establish a new type of dialogue with the native peoples and, in particular, with the Mapuche people.

THE LONG ROAD TO RECOGNITION

A century later, the return of democracy opened up hopes of a new understanding between the State of Chile and the Indigenous Peoples. That century had not meant much for the native peoples. The Nuevo Imperial agreement (1989) that brought together indigenous leaders with presidential candidate Patricio Aylwin established an opportunity for dialogue.

The indigenous people committed themselves to channel their legitimate aspirations for justice through the participatory bodies that would be created to advance in the solution of these problems. Candidate Aylwin committed himself to the constitutional recognition of the economic, social, and cultural rights of indigenous peoples; the creation of a National Corporation for Indigenous Development; and the creation of a special commission for Indigenous Peoples.

Thirty years passed and timid progress was made towards a legal institutional framework, innumerable commissions were created to address indigenous demands without much success and to this day the issue of constitutional recognition has not been resolved.

Since that time, a large part of the political and economic sectors that have administered power have favored "integration" policies, assuming that the great problem facing indigenous peoples are poor, marginalization and exclusion. The question of recognition has been consistently avoided, as this would imply accepting that there is an "other", peoples pre-existing the Chilean nation, who have the capacity and right to govern themselves, who have the right to autonomy, territory, cosmovisions, cultures, and different ways of relating to the natural environment.

Thirty years have passed since the return to democracy and despite the fact that most governments explicitly promised to recognize indigenous peoples, none has dared to establish a new type of relationship and dialogue.

Between 2016 and 2017, an indigenous constituent process and consultation with indigenous peoples took place. Discussions were generated that brought together more than 20 thousand indigenous people. What did they propose: Plurinationality, territorial recognition, recognition of pre-existence, autonomy, political representation rights, cultural and linguistic rights, health rights, among others.

What did the Bachelet government propose? In March 2018, it presented to the country a draft reform to the Constitution that in Article 5 stated:

"The State recognizes the indigenous peoples that inhabit its territory as part of the Chilean nation, obliging itself to promote and respect their integrity as such, as well as their rights and culture". It also recognized the right to participate with representation in Congress, as well as educational, cultural, linguistic, and patrimonial rights.

The second recent moment is 2017 Chile Vamos coalition program reiterated this denial of difference. Piñera's program argued that "the Chilean nation recognizes in indigenous peoples a relevant element of what characterizes our identity, both in our culture, our traditions and our history." While the indigenous peoples demanded recognition (social, political, territorial, cultural), the political elite was dominated by an integrationist ethos that made it impossible to resolve the conflict that had been latent since the origins of the Republic.

Even if in such proposals an "other" is accepted, it is immediately assimilated into our identity. Cultural traditions" are accepted but they do not threaten economic, territorial, or current political power distribution interests. In this way, a fundamental discussion on the way in which coexistence between different peoples in the same territory could be generated is avoided.

Chilean society, in fact, is very much in favor of this solution. A survey conducted by the Centro de Estudios Intercultural and Indigenous (CIIR) in the month of March 2020, shows that 97% are in favor of recognizing indigenous peoples. What is interesting here is the high support of the citizenry (indigenous and non-indigenous) for the materialization of certain political rights such as reserved seats in Congress (82%), having a special justice system (77%), returning lands (77%), defining indigenous languages as official (85%), the right to the consultation (77%) and the existence of reserved seats in the convention that will draft the new Constitution (82%).

The paradox of this story is that while the Minister of Defense announces the sending of the military to Araucanía, Minister Ignacio Briones offers us a radically different solution. In the interview with Cristián Warken in the ICARE dialogues, Briones argued that a long-term discussion was required, about what kind of society we need to build. He calls on us to be ambitious and think about Chile in the 20-year term:

"I like countries like New Zealand, which are not so far away in their level of development, but which are very remarkable in terms of opportunities, integration, inclusion. They share similarities with us, for example, they are strong in natural resources and are not ashamed of them. They are countries that integrate their native peoples. They are very open, competitive, pro-market countries. I am very interested in that paradigm" (Briones, 2020).

Do the authorities know that in the New Zealand model the State recognizes the pre-existence and self-determination of the Maori people? Do the decision makers in Chile know that the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840, which defined the relationship between the Crown and the Maori people, was recognized? Do they know that a tribunal was established to resolve the demands of the Maori people and that from there, policies of territorial devolution, protection of cultural rights and recognition of political rights were established? Among other institutions in New Zealand there is a Ministry of Maori Development, reserved seats were created, an office for the implementation of the Treaty of Waitangi was established.

Do the authorities know that in the New Zealand model the State recognizes the pre-existence and self-determination of the Maori people? Do the decision makers in Chile know that the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840, which defined the relationship between the Crown and the Maori people, was recognized? Do they know that a tribunal was established to resolve the demands of the Maori people and that from there, policies of territorial devolution, protection of cultural rights and recognition of political rights were established? Among other institutions in New Zealand there is a Ministry of Maori Development, reserved seats were created, an office for the implementation of the Treaty of Waitangi was established.The recognition process in New Zealand has been going on for more than three decades and has involved compensation policies for the damage caused to Maori communities, recognition, and public apologies from the authorities regarding the breach of the original treaty, and the establishment of cultural, commercial and financial compensation mechanisms. The New Zealand model that Minister Briones likes so much contains not the "integration" of native peoples but rather a process of symmetrical, long-term dialogue between two peoples (Gálvez 2019). If there is a genuine interest in following the New Zealand model, the State of Chile should start by recognizing the Treaty of Tapihue of 1825 and advance policies of reparation for the damage caused.

In Chile, the political and economic elites have historically opted for assimilation, integration, or repression. There has been no long-term vision that accepts and substantively recognizes the native peoples that inhabit the territory. As long as that substantive recognition does not take place, we will continue to be anchored in an integrating and militaristic paradigm that is much closer to what the conquistadors Saavedra, Pinto or Vicuña Mackenna envisioned, than to a foreign ideal about which little is known.

The use of the armed forces is the failure of politics and in this case it seems evident that politics -in its broad sense- has failed.

References

Briones, Ignacio. 2020. Interview by Cristián Warken in the program "En Persona", Icare, June 21, 2020.

Gálvez, Melisa. 2019. Políticas de reconocimiento indígena: lecciones del caso de Nueva Zelanda y el pueblo maorí. ICSO Working Paper No. 56.

Saavedra, Cornelio. 1870. Documentos relativos a la Ocupación de Arauco que contiene los trabajos practicados desde 1861 hasta la fecha por el coronel de Ejército, don Cornelio Saavedra. Santiago: Imprenta Libertad.